Investor Insights

SHARE

Could a credit crunch be more important than a recession?

I have just penned my next column for The Australian Wealth section this weekend. In the article I explain how different definitions of recession are common and yet largely irrelevant for today’s equity investor.

Some say its two quarters of negative growth. If that’s the case, then the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow tool is predicting the U.S. is in a recession. Meanwhile, the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research says a recession is a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months. If that’s the case the 488,000 new jobs created in May would void any assessment of recession.

Elsewhere, given inflation is at nine per cent in the U.S., and growth is a far cry from that number, the real economy is going backwards, validating the person-in-the-street’s perception of recession. And finally, the U.S. yield curve has just gone negative, confirming an economic slowdown.

Central banks are in a quandary

Even though economies appear to be losing momentum, inflation remains unacceptably high. And even though we might be near a peak in inflation, the decline is unlikely to be fast enough to placate Central Banks. Consequently, I agree with the idea downside surprises in inflation are the outcome of recession, not an indicator we will avoid one – whatever your definition of recession actually is.

The last time U.S. inflation was this high was 1981, but as analyst Ben Carlson points out the circumstances are very different.

In 1981, savings accounts offered a 10 per cent yield (today they provide a one per cent yield). Mortgage rates then were 17 per cent, today they are five per cent. In 1981 U.S. treasury bond yields were 13 per cent, today they are at three per cent. And finally, Robert Shiller’s Cyclically Adjusted P/E ratio was just eight times in 1981. Today it’s still at 28 times.

There are a multitude of differences today to any other time in history. Searching the past to discern what happens next may be a fools errand.

Instead, I believe it is most important to look to liquidity. Giant swings in the availability of money, especially in modern debt-based financial systems, do more to explain the vicissitudes of markets than macroeconomics.

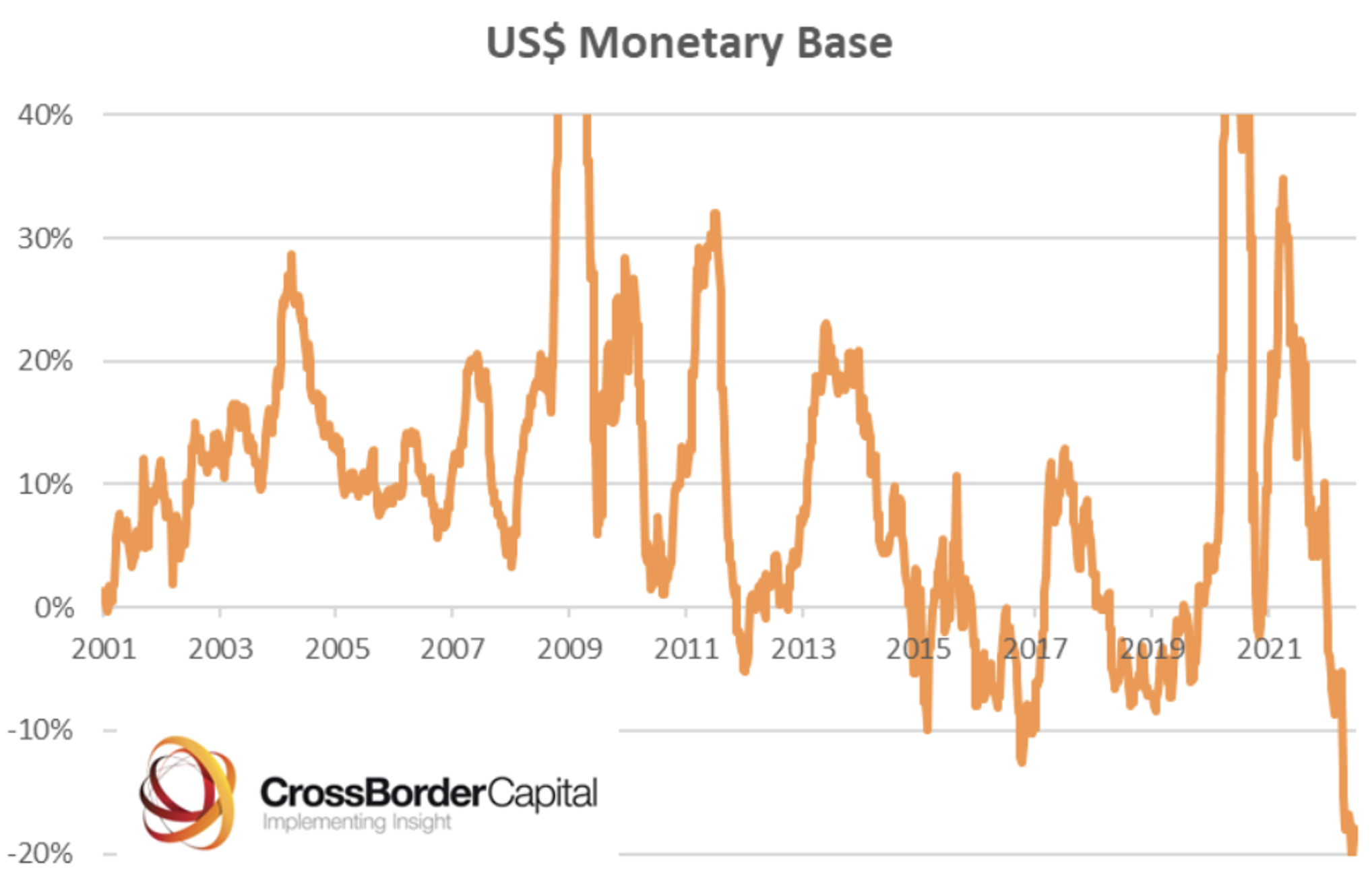

And on that front, Crossborder Capital’s chart of the liquidity cliff in the supply of the USD worldwide, including off-shore, suggests a major credit crunch is ahead.

Source: Crossborder Capital

And according to Michael Howell, “The economic cost of this big liquidity squeeze is world recession” adding “Central Banks are making a major error by hammering down too hard on the brake. World recession is inevitable.”

Meanwhile the U.S. Treasury yield curve is seeing collapsing term premia. The term premium is the amount by which the yield on a long-term bond is greater than the yield on shorter-term bonds. Collapsing premia means short term rates are rising at a higher rate than long term rates. The mix of higher front-end rates raises cost of capital for corporates, while lower rates at the long end of the yield curve reflects meaningful demand for safe assets. In other words, no appetite for riskier corporate debt. In combination, it suggests a credit crunch is afoot. It’s arguably much more important than whether we are heading for a recession – whatever your definition.