Investor Insights

SHARE

Perreault Resigns from CSL, having already written some of the next chapter

When investors, like Montgomery, and our partners, Australian Eagle, talk about quality Australian companies – those with wide and deep economic moats or competitive advantages, relatively low debt, high returns on equity and growing profits – Australian biotech CSL Limited (ASX:CSL) invariably appears near the top of the list. Even global quality-based investors such as Polen Capital count CSL among their holdings.

CSL is a global leader in the manufacture of flu vaccines and in the highly regulated market for blood plasma derivatives from which immunodeficiencies and Haemophilia, for example, are treated. CSL operates a global network of blood collection centres, fractionating the blood into its separate components, which become the base for life-saving treatments and specialty products for immunodeficiencies, bleeding disorders, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, as well as hereditary angioedema and Alpha 1 Antitrypsin Deficiency.

CSL benefits from high barriers to entry

CSL benefits from a spaghetti-like network of global regulation and capital intensity that together form meaningful barriers to entry. CSL’s scale enables a higher level of sales than competitors, which in turn affords it the ability to invest circa 10 per cent of its sales on Research and Development. This allows CSL to commercialise more products from each litre of plasma it collects, leading to even higher sales and margins. CSL reinvests this cash in investments and acquisitions that may ultimately drive significant future growth opportunities.

CSL’s CEO, Paul Perreault, joined CSL in 2004 with the acquisition of Aventis Behring. Prior to CSL, he had spent more than 15 years in key senior roles at Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories, now part of Pfizer. Perreault was appointed Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director of CSL Limited in July 2013 and was appointed to the CSL Board of Directors the same year. Since Perreault’s appointment, CSL has grown to become the third-largest biotech company in the world, with more than 30,000 employees bringing lifesaving medicines to people in more than 100 countries.

In early 2020, under Perreault’s leadership, CSL briefly pipped Commonwealth Bank and BHP Billiton – excluding the mining giant’s then London-listed shares – as the biggest listed company on the ASX.

CSL’s performance under Paul Perreault

Perreault however has just announced he will step down from his role in March 2023.

We thought it worthwhile measuring CSL’s performance during Perreault’s tenure, helping to set some benchmarks for his successor, current COO Paul McKenzie.

For the year ended 30 June 2013, the day before Perreault’s appointment as CEO, CSL had equity on its balance sheet of US$3.4 billion, generated US$1.22 billion of earnings, and a return on average equity of 37.5 per cent. In the nine completed years since then, earnings have grown 85 per cent (7.1 per cent p.a.), total dividends have grown 108 per cent (8.4 per cent p.a.), US$2.7 billion of net equity has been raised (US$5.1 billion of that amount was raised last year) and almost $8 billion of debt has been raised (almost half of it raised last year).

The large equity and debt raised in the 2022 financial year helped fund CSL’s December ’21 acquisition of Vifor Pharma, diversifying its predominantly vaccine and blood plasma business into kidney disease and iron deficiency franchises. With the fruits (or otherwise) of that acquisition unlikely to be fully realized and harvested by CSL investors for some years, it is sensible to adjust our numbers when assessing Perreault’s performance to exclude the year of the most recent capital and debt raisings. We, therefore, assess performance over the years 2014 through 2021. In five years or so, it would be useful to reassess the numbers, painting a picture of the Perreault/Vifor legacy.

Re-examining the numbers over the eight years from 2014 to 2021, we find, under Perreault’s stewardship, profits have grown 95 per cent (8.7 per cent p.a.), dividends have grown 92 per cent (8.5 per cent p.a.), earnings have exceeded dividends by US$8.5 billion, which has been retained, US$2.3 billion of equity has been bought back and US$4.1 billion of debt has been raised.

With the change in issued capital being a negative number, we cannot calculate a sensible result for Return on Incremental Capital (ROIC). Suffice to say, Perreault has managed to double CSL’s earnings while reducing, through share buybacks, the equity required to produce those earnings. Without the buybacks, equity at the end of 2021 would have been 50 per cent higher. This is, without question, an impressive result.

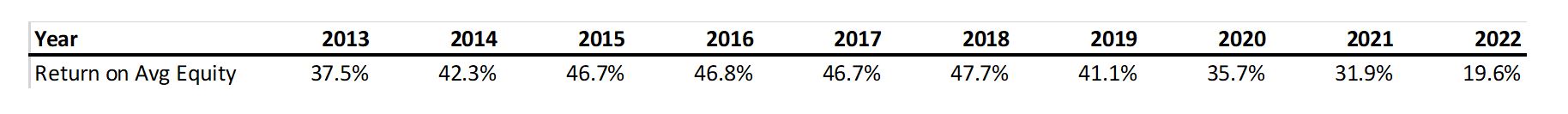

There is, however, the small matter of debt; interest-bearing liabilities have risen by US$4.1 billion, with half of that amount raised in 2015, 2016 and 2017. The debt, of course, does help to boost return on equity and the return on equity picture is shown in Table 1.

Given 42 per cent of earnings were paid out in dividends, during the period of Perreault’s tenure, we can say the retained earnings were sufficient to entirely fund the share buybacks. Nevertheless, some of the debt, it could be argued, has served to boost return on equity.

Table 1. CSL Return on Equity during Perreault’s tenure

Table 1., reveals Perreault’s tenure coincided with a substantial initial rise in return on equity (ROE). After taking over the helm of a business generating a 37.5 per cent ROE in 2013, Perreault drove CSL’s ROE much higher, reaching a peak of 47.7 per cent in 2018. Since then, ROE has declined to below 2013s level but still an impressive 31.9 per cent in 2021; remember, this is now a much larger business. As an aside, for 2022, Table 1. shows the ROE based on average equity, remembering a very large equity raise occurred to help fund the Vifor acquisition. Suppose we use beginning equity instead of average equity as the denominator in our calculation. In that case, the return on equity is more impressive, but it fell for another consecutive year, to 26.9 per cent.

Whether or not the job of maintaining returns on equity of over 30 per cent, and therefore the pace of value creation, is becoming more difficult, time will prove the arbiter. Perreault can point to a ten-year track record of impressive returns, solid growth in earnings and dividends, a share price that has risen approximately 367 per cent and, hopefully for McKenzie, a new source of impressive returns and growth in Vifor.

Based on 2022 beginning equity, we can agree that Perreault leaves CSL returning 26.9 per cent on equity. He has also grown profits and dividends at an average annual rate of roughly seven per cent and 8.4 per cent, respectively, over the nine years since the end of the 2013 financial year, equity has been reduced through net buybacks of US$2.3 billion, but debt has risen from US$1.7 billion in 2013 to US$9.7 billion in 2022, thanks substantially to the Vifor acquisition. Returns on equity and capital have been declining annually since 2018, and this possibly explains the share price being virtually unchanged for almost three years.

Overall, it is an impressive track record. Still, the acquisition of Vifor and its impact on equity, debt, and return on equity also means Perreault’s track record shouldn’t end with his departure. For serious investors, one of CSL’s key metrics (future ROE) largely hangs on the Vifor acquisition, which is substantial in its size and impact on the balance sheet. Vifor was acquired for US$12.3 billion and is expected to contribute US$330 million to NPAT for 11 months in 2023. On an annualised basis, that’s a return on the purchase price in year one of just under three per cent.

Some might argue a CEO’s reputation should continue to be weighed on the future performance impact of a substantial acquisition made a little more than a year before that CEO’s departure. Could CSL’s next chapter have already been substantially written? If so, the previous CEO remains the co-author, if not the author.

Isolating responsibility for the subsequent performance of a major acquisition is challenging when a new CEO takes over the strategy and operations. But unless the new CEO, while in his former role as COO, was solely responsible for that acquisition and the price paid, they cannot be held solely responsible for subsequent changes in ROE and, therefore, value creation.

In 2015, when CSL purchased the Novartis influenza vaccine business for US$275 million, combining it with BioCSL to create a new CSL subsidiary called Seqirus, many believed too much was paid. At the time of the acquisition, while Novartis might have been the global leader in cell-based (rather than hen egg-based) influenza vaccines, it was highly unprofitable. CSL turned it around to create a profitable leader in cell-based vaccines, the importance of which was highlighted by the pandemic in 2020 and 2021. In FY22 Seqirus represented 25 per cent of CSL’s 25 per cent of profit, generated revenue growth of 13 per cent to US$1,964 million, EBIT growth of 52 per cent to US$735 million, and a 630 basis-point increase in EBIT margin to 37.4 per cent.

With Perreault’s resignation, the performance of Vifor will become his legacy and is something CSL investors will watch keenly. In the years to come, Vifor’s performance will play a large part in whether the impressive 367 per cent growth in the price of CSL shares during Perreault’s tenure is repeated.

The Montgomery Funds own shares in CSL. This article was prepared 15 December 2022 with the information we have today, and our view may change. It does not constitute formal advice or professional investment advice. If you wish to trade CSL you should seek financial advice.