Investor Insights

By , Roger Montgomery

SHARE

How to minimise risk during recessions and economic crises

What’s the best way to minimise risk when investing during a recession or economic crisis? Research by NYU’s Stern School of Business shows that one method could be to allocate funds according to where the company sits in its business lifecycle – which is the approach taken by the Montgomery Small Companies Fund.

Researchers often study particular sectors and compare their performances in an attempt to glean how to invest through a recession or an economic crisis. For example, between mid-February and mid-June this year – the period that takes in the COVID-19 crisis sell off and the subsequent rally – Financials in the US was the single worst performing sector, followed closely behind by Real Estate and Energy, Utilities and Industrials. The best performing sectors during this four-month period were Healthcare and Information Technology.

The problem with this simple analysis is that each recession or crisis can be a little different and the past is often not a reliable guide to the future. And not only is the nature of each crisis different but so are the participants. The rise of commission-free brokerage firms combined with lockdowns means a huge number of people who would typically gamble on sports matches or at casinos migrated to the stock market and to a relatively narrow band of liquid companies potentially skewing the results.

Another way of looking at how a crisis might impact investment returns that may have more explanatory power is to think about where a company is in its lifecycle.

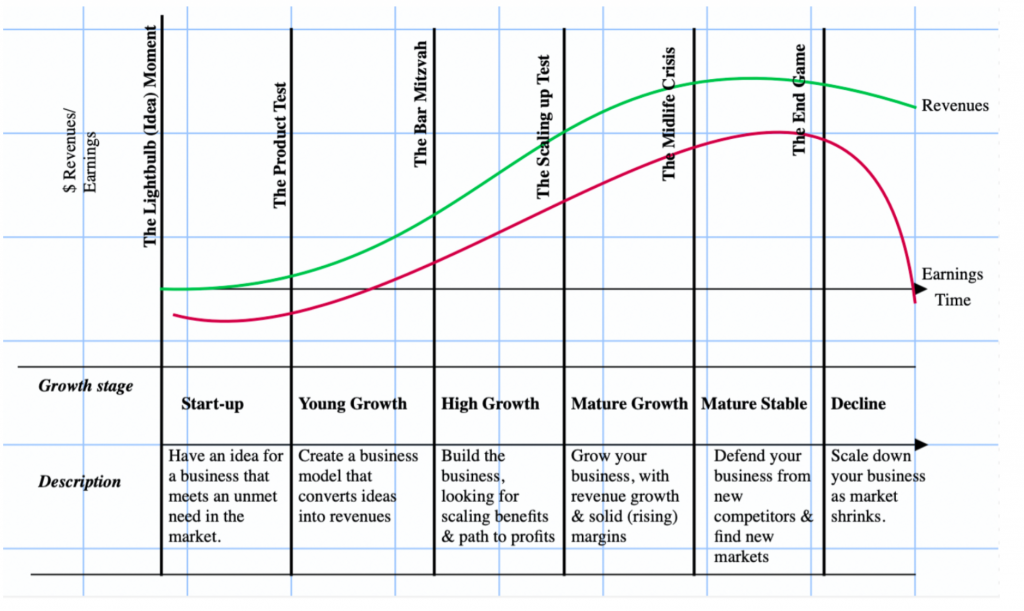

The textbook lifecycle is shown in Figure 1 and the relevant cashflows in Figure 2.

Figure 1. The typical corporate lifecycle

Source: NYU Stern School of Business

Figure 2. Corporate lifecycle cashflows

Source: NYU Stern School of Business

Aswath Damodaran, at the Stern School of Business at NYU, makes the observation that a crisis affects companies differently depending on the stage of their lifecycle.

For start-ups and very young companies, a crisis delivers a mandate to merely survive. With little or no revenue, start-ups require capital but during a crisis access to capital can dry up as investors prioritise liquidity.

For young growth companies – those still in the early stage of their lifecycle but generating marginal profits – access to capital remains vital for faster-than-organic growth. If access to capital becomes challenged, the typical response according to Damodaran is to scale back growth ambitions.

Mature firms are hit in the balance sheet by a crisis. As the economy slows or slides into recession, and consumers cut back on spending, the carrying value of assets is hit with the impact greater on companies selling discretionary products than those selling consumer staples.

Finally, for declining firms, especially those that have hitherto been shoring up their competitive position by accumulating debt, a crisis can tip them into distress, default and bankruptcy. If risk premiums rise and access to capital tightens, the path to distress is more rapid, if not inevitable.

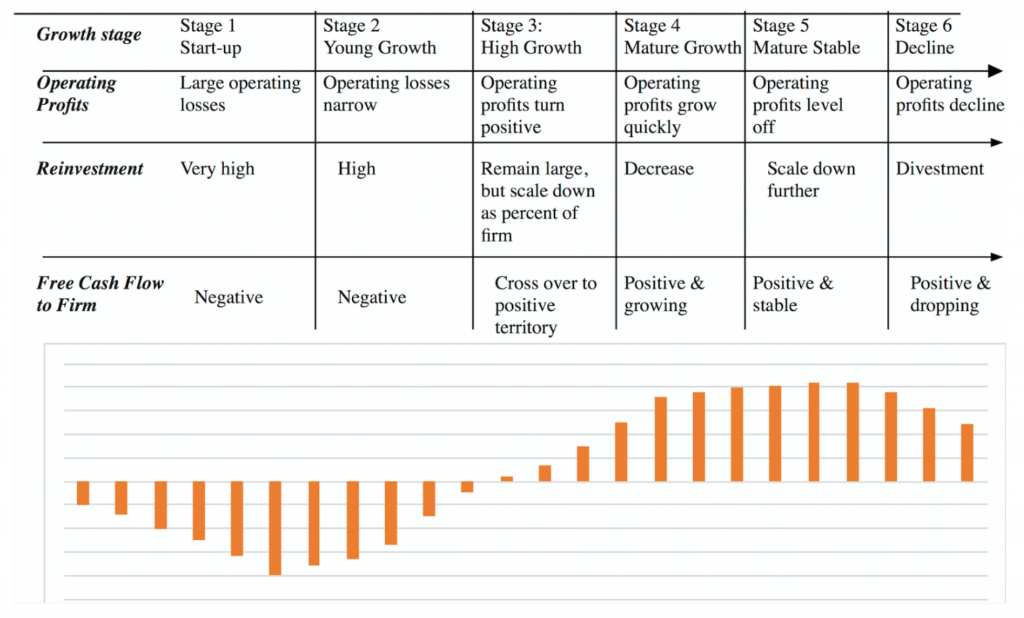

When Damodaran split the market up by company age and by expected revenue growth (instead of by sector or industry) a potentially useful finding was revealed.

When categorised into deciles by company age, the fifth decile companies had performed best between mid-February 2020 and mid-June. The oldest decile of companies performed worst. See Figure 3.

Figure 3. Young versus old companies

Source: NYU Stern School of Business

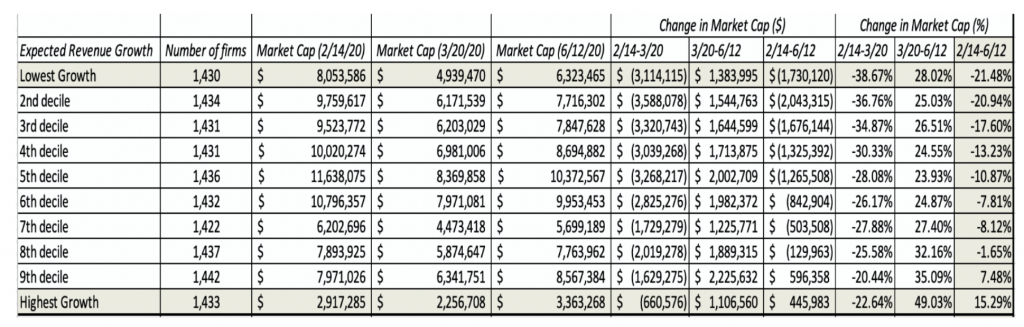

When categorised into deciles by expected revenue growth (Figure 4.), the highest growth companies performed best and the lowest growth companies performed worst.

Figure 4. High growth versus old growth

Source: NYU Stern School of Business

Notably, low interest rates are not mentioned in Damodaran’s presentation. Declining interest rates have a materially greater impact on the intrinsic value estimate of companies with cash flows expected further out in time. For a given drop in interest rates, the present value of a dollar earned in five years rises by less proportionately than a dollar earned in twenty years. If all crises were accompanied by declining interest rates, the theory that one is better off in high growth companies, or even earlier-stage companies would hold.

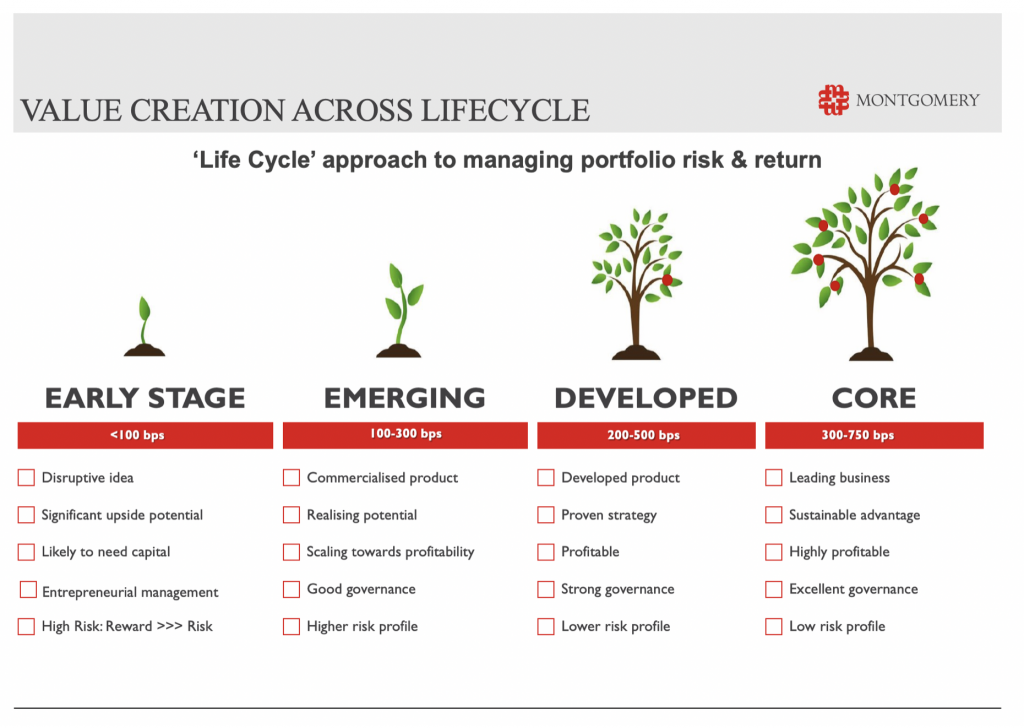

Figure 5. Montgomery Small Companies Fund investable universe

Figure 5. shows a slide from the Montgomery Small Companies Fund’s explaining how the team slices and dices the market by growth stage for the purposes of capital allocation. Weightings of less than 100 basis points are given to companies in the Early Stage, while higher weightings are given to companies as survival risk declines.

Of course, for Damodaran’s conclusions to be robust the NYU research would also need to look at out-of-sample data. In other words, do we find the same relative performances in other markets and economies? Are the conclusions the same when observing UK companies or Australian companies? If the conclusions in other markets concur with those in the US study, then there is another very good reason to invest in a small companies fund – yes, like the Montgomery Small Companies Fund. We certainly think there is.

The Montgomery Small Companies Fund return since inception (20 September 2019) has exceeded The Fund’s benchmark, the S&P/ASX Small Ordinaries Accumulation Index, by 12.11 per cent to 30 June 2020. For an update on the recent performance, please review this article.