Investor Insights

SHARE

House prices not getting cheaper anytime soon

For almost a decade, I have described Australian residential property owners as a “protected species”; Whether we look at the banks, the banking system in its entirety, regulators, including the Australia Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), the government and even individual politicians – many of whom own multiple residential investment properties – nobody wants to see property prices fall.

Governments have incentivised people to buy residential property through various first home buyer schemes and other tax incentives. The banking system’s very stability is reliant on residential property, which makes up the lion’s share of the major banks’ balance sheets, and many individual politicians’ largest asset allocation is in residential real estate, dissuading them from making any changes to property-related taxes that would result in adverse price changes.

And now, even the supply and demand picture supports house prices rising further and rendering affordability more acute than ever.

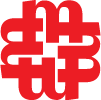

Figure 1. Average Australian house prices and capacity to pay to December 2023

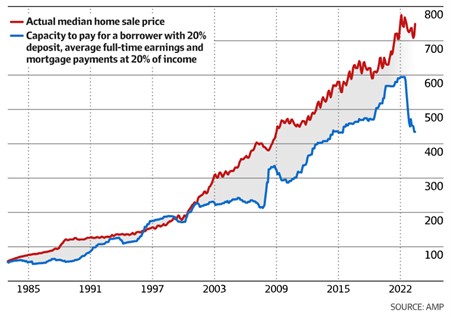

stralians have it pretty tough compared to the rest of the world, too. Figure 2., from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas in the U.S., while dated to 2018, reveals house prices, since the 1970s, have risen the most for Australians compared to per capita income than the average for 23 other developed nations. In Australia, house prices-to-income are four times greater than house prices-to-income were in the mid-1970s.

stralians have it pretty tough compared to the rest of the world, too. Figure 2., from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas in the U.S., while dated to 2018, reveals house prices, since the 1970s, have risen the most for Australians compared to per capita income than the average for 23 other developed nations. In Australia, house prices-to-income are four times greater than house prices-to-income were in the mid-1970s.

That could be because either our salaries haven’t risen as much as elsewhere in the world (unlikely) or, despite our ‘land of sweeping plains’, we have a combination of policies and processes – including tax and development, respectively – that have uniquely combined to push house prices up much more relative to incomes than elsewhere.

Figure 2. House prices versus per capital income, Australia vs developed world

Source: Dallas Federal Reserve Quarterly database of Real House Prices, BBC.

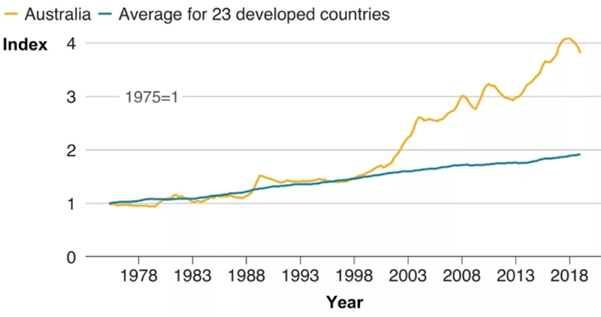

Since 2018, and adjusting for inflation (Figure 3.), an equally gloomy picture appears and helps explain why our younger generations do have it so tough – and it clearly has little if anything to do with avocado on toast!

Figure 3. Australia real household disposable income per capita vs real house price index

Source: Tarric Brokker, St Louis Fed, ABS.

Nevertheless, according to the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) last week, things aren’t likely to improve for would-be buyers anytime soon. The central bank issued a stark warning last week about the ongoing surge in property and rental prices, attributing the issue to a confluence of rising construction costs and higher interest rates, which are significantly impeding the delivery of new housing supply. And you can add development red tape to that list.

At a recent event in Hobart, RBA Chief Economist Sarah Hunter highlighted the persistence of these challenges, describing them as a “perfect storm” that continues to restrain construction activity. “Despite navigating the pandemic’s disruptions, the sector now faces weaker demand, with dwelling approvals per capita at decade-lows,” Hunter noted. She pointed out that many developers are postponing or cancelling projects due to the high construction costs relative to expected returns.

Since late 2019, the costs of building materials and labour have skyrocketed by nearly 40 per cent, making numerous residential developments economically unfeasible. The sharp rise in the official cash rate, which has climbed from 0.1 per cent to a 13-year high of 4.35 per cent in just 18 months, has exacerbated this issue by increasing funding costs for new projects.

The RBA is also keen to remind us that inflation remains a pressing concern, with the latest consumer price index (CPI) showing a one per cent rise during the March quarter, bringing the annual inflation rate to 3.6 per cent. While this is a decrease from the peak of 7.8 per cent, it remains above the RBA’s target range of 2-3 per cent. The federal government’s latest budget includes measures like a $300 power bill rebate and increased rent assistance, which Treasurer Jim Chalmers claims will reduce headline inflation. However, economists and I are understandably sceptical about the idea that handing people cash brings down inflation. A power bill rebate releases $300 to spend elsewhere.

Meanwhile, the decline in building approvals underscores the severity of the housing supply crisis. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), new home building approvals fell by 9.5 per cent in December, with a sharp 25.3 per cent drop in apartment and unit approvals. This is shocking for would-be buyers and will be terrible for some time, however, the Urban Development Institute of Australia has more diplomatically noted, “This is the worst time to see building approvals declining and reflects the magnitude of the task ahead to increase housing supply and alleviate price and rent pressures.”

Despite a recent stabilisation, building costs remain over a third higher than pre-pandemic levels, compounded by ongoing labour supply issues. As Master Builders Australia confirmed, the continued cost pressure frustrates efforts to expand the stock of new homes.

Elsewhere, a slowdown in new home lending has further complicated the situation. In 2023, lending for new home construction or purchase fell to its lowest level since 2002, with just 51,570 loans issued, less than half the number from two years earlier. The Housing Industry Association attributed this decline to the RBA’s aggressive rate hiking cycle, which has squeezed potential homebuyers out of the market and stymied new home commencements.

As the federal government targets ambitious housing goals, the focus now shifts to state-level initiatives aimed at streamlining approvals and reducing building costs. These will, however, meet with resistance because infrastructure spending is unlikely to meet the needs of higher density in many areas, reducing quality of life. The RBA’s Sarah Hunter also cautioned these measures will not provide an immediate solution, stating, “until new supply comes online, demand pressure will continue to drive up rents and prices.”

Residential construction activity will remain subdued for the foreseeable future, keeping prices elevated and out of reach for many if not most of the generations that have yet to buy.