Investor Insights

SHARE

Could the strengthening USD trigger a financial crisis?

Dysfunction, disorderly, crisis, financial shock. These are not the words investors want to hear, but they are increasingly on the minds of some economists, analysts and investors. So, what factors have led to such a negative outlook?

It begins with everything we have written about here at the blog already. The U.S. Federal Reserve has been playing ‘catch-up’, raising rates faster than others, and at a pace unseen in decades. Additionally, the U.S. central bank has adopted a policy of balance sheet reduction, also known as QT (Quantitative Tightening), which involves allowing the bonds it has previously purchased to mature without replacing them, and which has a similar effect to rate tightening albeit further out along the yield curve.

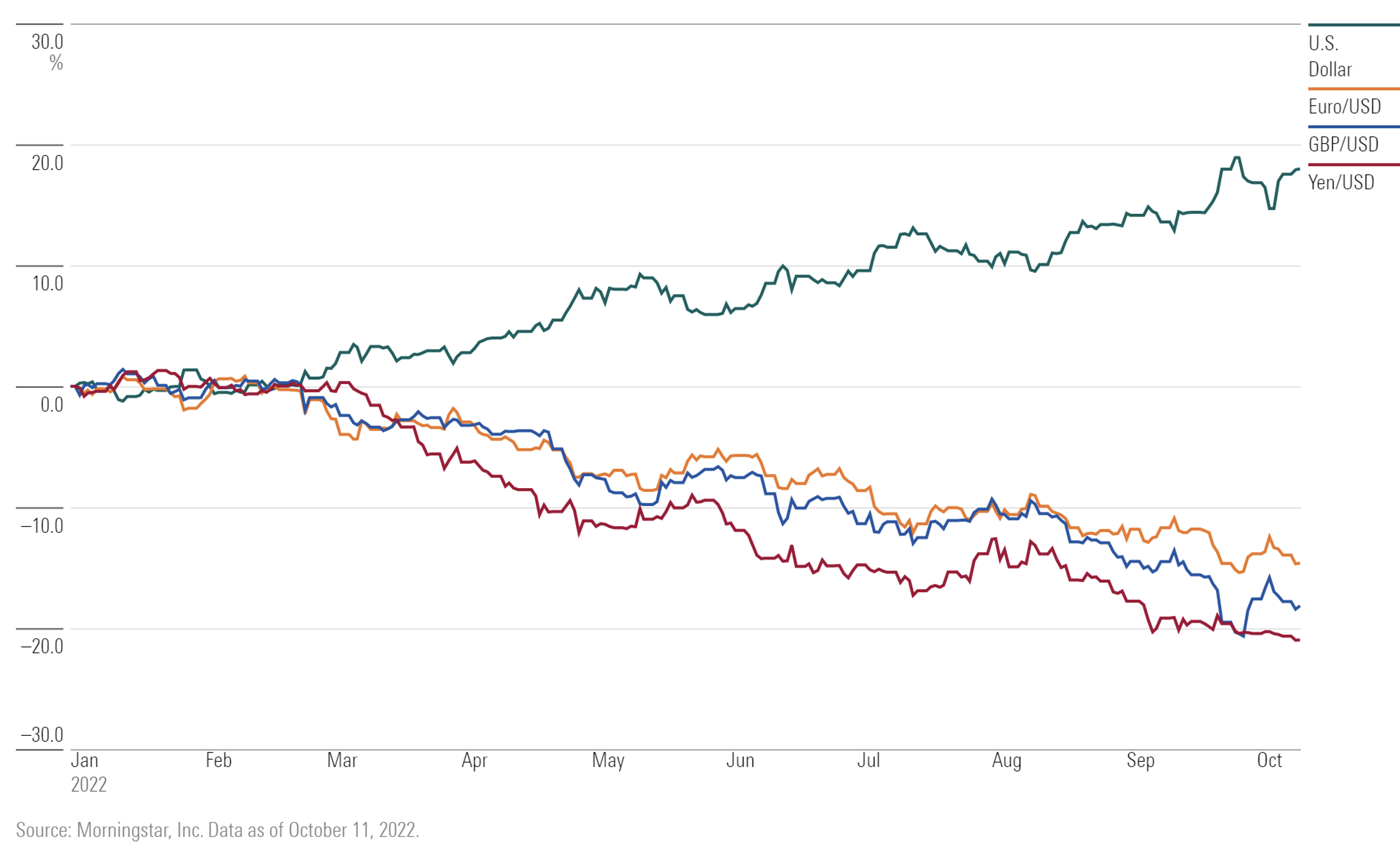

It’s all part of that central bank’s plan to get their balance sheet down and the U.S. dollar up. And it’s worked. Figure 1 reveals the resultant dispersion between the U.S. dollar and its main trading cross currencies.

Figure 1. USD Performance

For many, there’s safety in owning U.S. dollars because the Federal Reserve’s Chairman, Jerome Powell, has repeated the refrain the bank will uphold its forceful stance, and “keep at it” until inflation has been tamed.

The global consequence of U.S. dollar strength is currency cross-rate weakness. The weaker currencies effectively paint the U.S. as the exporter of inflation. And some analysts believe this raises the threat of default, especially by those developing countries with large dollar-denominated debt balances. According to the United Nations (UN), 90 per cent of emerging market debt is denominated in U.S. dollars, so a stronger USD renders repayments punitive. Meanwhile, global debt levels reached a 50-year high following government fiscal initiatives to support society during the pandemic.

In May 2022, Sri Lanka – considered a middle-income country – defaulted on its debt for the first time. The country’s government was given a 30-day grace period to cover $78 million in unpaid interest but ultimately failed to pay, amid heaving inflation spurred by the collapse of its currency.

Indeed, a record number of developing countries are now in difficulty if the measure is a combination of collapsing currencies, bond spreads blowing out beyond 1,000 points, and torched FX reserves. Joining Sri Lanka for example are Lebanon, Russia, Suriname, and Zambia. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) now estimates almost a third of emerging market countries and 60 per cent of low-income countries could face trouble paying down their debts or will soon.

Rising borrowing costs, inflation, and debt all fuel concerns of an economic collapse for many countries. The UN has called for debt relief for 54 developing economies it has identified as experiencing severe debt problems. And while these countries account for just over three per cent of the global economy, they represent 18 per cent of the global population and over half of those living in extreme poverty.

The idea of a financial crisis has raised its head in developed markets because it was until now thought the debt default issue and corresponding bond market volatility was contained within developing countries. Huge swings such as those experienced by the UK Gilt market in late September typically don’t happen to the sovereign debt markets of developed countries.

In the recent UK episode, thanks in no small part to the plunge in Cable (British Pound/USD) amid fiscal irresponsibility, the 30-year Gilt yield rose by 160 basis points in just four sessions and then collapsed by 400 basis points in one. As recently as the week before last, the Bank of England was expanding its bond buying program despite the fact it is scheduled to end at the end of this week.

The uncertainty for many, and the very real financial pain for many more, is understandably causing concerns and associated volatility.

Watch this space.

You can read other thoughts on the USD in this article:

WHAT WILL ROAR WHEN THE USD EVENTUALLY REVERSES?